Banking on Meme-iotics: Visual Free Speech between the Judge’s Gavel & a hard rock.

“The removed Banksy says more about England now than it did before its removal”

Joker @BachelorJoker

2:20 AM · Sep 12, 2025

Libertarians generally dedicate themselves to a sound education in economics, history, and moral philosophy. One area of study that can be overlooked, however, is Art! Libertarians, of course, value Free Speech and open discourse—hence their respect for the mission of Charlie Kirk. The neglect of art in a libertarian curriculum, however, is curious, as art, in one sense, can be viewed as visual speech, and it certainly gives rise to discussion!

I say neglect, but in truth, I really mean a lack of in-depth investigation and study. Many libertarians do in fact understand the significance of the visual regardless of any formal training. There is the adage, “The left cannot meme.” This is as much a testament to the creativity and power of online imagery that libertarians disperse as it is a criticism of the poor quality of leftist imagery (and argument).

On the other hand, many libertarians, particularly the more conservative-leaning kind, tend to respect more traditional art (pre-modernist, before circa 1890). That is, art that can be considered to be mimesis (imitation) in representation. Couple this limitation with authoritarianism and a certain infamous 20th-century political movement in Germany, which declared all modern art as degenerate, comes to mind. While it is true that much of Post-modernist and contemporary art, and even a lot of the Modernist era, is worthy of great criticism, and perhaps rejection, it is important not to throw the baby out with the bathwater due to a lack of visual education—understanding.

Art is visual communication—a visual language. A limitation in language is a detriment to communication. A lack of vocabulary can restrict one’s ability to convey meaning and express emotion. The same can apply to visual literacy. I would argue that a deeper study of the visual can greatly contribute to a libertarian education and understanding of communication.

One aspect of the vocabulary of visual language is Semiotics. Semiotics is the study of signs and symbols. It plays a crucial role in how we construct, interpret, and communicate meaning. It emphasizes the importance of the signifier (the form or medium of the art) and the signified (the meaning or concept behind it). Online meme culture and some forms of street art expertly utilize the power of semiotics. Banksy and the recent court house artwork is a case to examine.

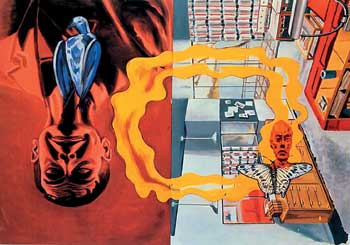

However, let us firstly explore one of the first modernist movements to embrace semiotics—the Capitalist Realists. The term “Capitalist-Realism” is a play on the earlier art movement known as “Socialist-Realism.” Socialist-Realism was the officially sanctioned art style in the Soviet Union, characterized by its idealized and propagandistic depictions of socialist life and values.

“Capitalist-Realism,” on the other hand, is a term coined by the German artist and theorist Gerhard Richter. It refers to a style of art that emerged in West Germany in the 1960s, in response to the consumerist and capitalist society of the time. The term is ironic and critical, suggesting that just as Socialist-Realism was the art of the socialist state, Capitalist-Realism is the art of the capitalist state. The imagery of the Capitalist-Realists, however, was not limited to that of hyperbolic heroic figures and overt propaganda. The movement, like Pop Art, was characterized by its engagement with the visual culture of capitalism, often incorporating elements of advertising, mass media, and popular culture.

Artists associated with Capitalist-Realism, such as Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter, used techniques like blurring, obfuscating, negation, distorting, and layering to (allegedly) critique the superficiality and alienation they saw in consumer society—yet simultaneously lionizing and indulging in the popular imagery of a Capitalist free society. Whatever the case, their work often challenges viewers to question the nature of their contemporary world. The techniques they employed are still used today, be that deliberately or accidentally.

We see censorship in such things as redacted documents. The obscured text shows us something is hidden. In economics, we have Bastiat’s lesson that there are always unseen consequences to any action, which are often overlooked in favor of the immediately visible outcomes. It takes a critical examination to reveal the unseen and consider other effects.

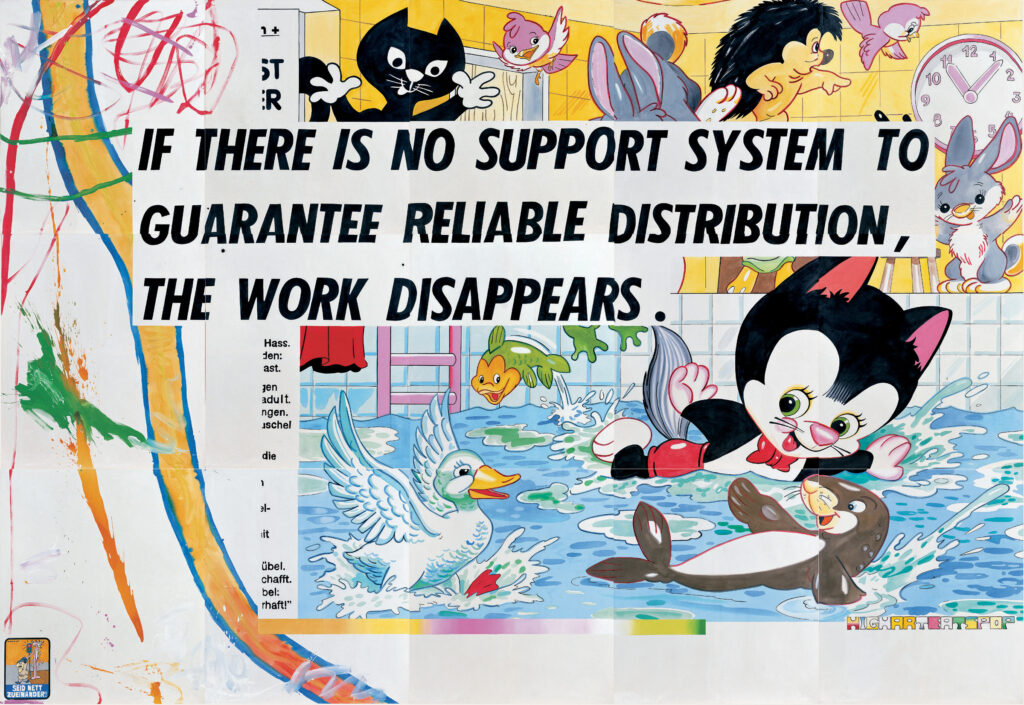

In the realm of art, obfuscation and layering and other techniques serve as a function of critical examination by peeling back the layers of the “seen” to reveal aspects of the “unseen,” hint at what is not there, or spark imagination in order to fill in the missing blanks. Art through semiotics becomes a discussion (free speech mechanism) to ask questions about truth or meaning.

The work of street artist Banksy is semiotically charged. The recent removal of a Banksy artwork from a court house in London, however, adds another layer of meaning—ironically through the removal of its primary layer! Putting aside the complexity of property rights in the public sphere, the shadowy remains blatantly expose the censorship of the state. What remains is a ghostly reminder of what was there. Not unlike an official public artwork program in Newcastle, Australia, where shadows were painted on walls to commemorate the fatalities of an earthquake.

The remaining remnant of the mural becomes a haunting reminder of the original message, but is now layered with extra salient meaning to heighten its effect. The fallen protester now somewhat resembles a crusader. The raised sign is transformed into a pitchfork or sword held against a barbarian with a war hammer—previously a judge with a gavel.

This outcome is often referred to as the “Streisand Effect.” The phenomenon where government censorship or suppression of information ironically leads to increased interest or attention. The Streisand Effect highlights the paradoxical outcome of censorship efforts, where the attempt to hide or suppress information can backfire, leading to greater visibility and interest.

In the context of other recent events, the painting over of a Charlie Kirk memorial serves as a stark example of how obfuscation can be used to enhance a powerful message. By defacing the memorial with Kirk’s own statements, activists have transformed the space into a site of semiotic contestation. The original memorial, intended to honor Kirk and his legacy, is now a site of political disputation, where the inscription of his words and actions are given the Streisand Effect through the imposition of a counter-narrative. This act of obfuscation arguably turns the memorial into a more profound symbol of the broader struggle to do with free speech (and other issues).

Interestingly, the defaced memorial in question has transformed from a simple monument into something resembling more of the expressionistic work of the Pop Artists Robert Rauschenberg and Claes Oldenburg due to the mistreatment of the surface.

Semiotics offers a valuable framework for understanding the complex dynamics of (visual) speech, meme culture, and the power of imagery. From the removal of a Banksy artwork to the painting over of a Charlie Kirk memorial, these recent events demonstrate how visual symbols can be used to challenge authority, question narratives, spark conversation, and construct meaning.

As we continue to engage with the symbols and signs that the world thrusts upon us, the principles of semiotics will remain crucial in helping us make sense of the messages they convey. By understanding how meaning is constructed and contested, we can better participate in the ongoing dialogue about free speech, art, and the power of visual communication.

The work of the Capitalist Realists serves as a great starting point for an investigation into the concept of semiotics. The Barking Bandicoot Academy will be releasing a course on this in 2026 to delve more deeply into the use of signs and symbols along with other art concepts.